MSU researchers leading the way in targeted land management

Between self-driving tractors, pest-targeting drones and robotic harvesters, Mississippi State has long been a leader in precision agriculture. While its counterpart—precision conservation—is lesser known, Bulldog scientists are ensuring it has just as large of an impact.

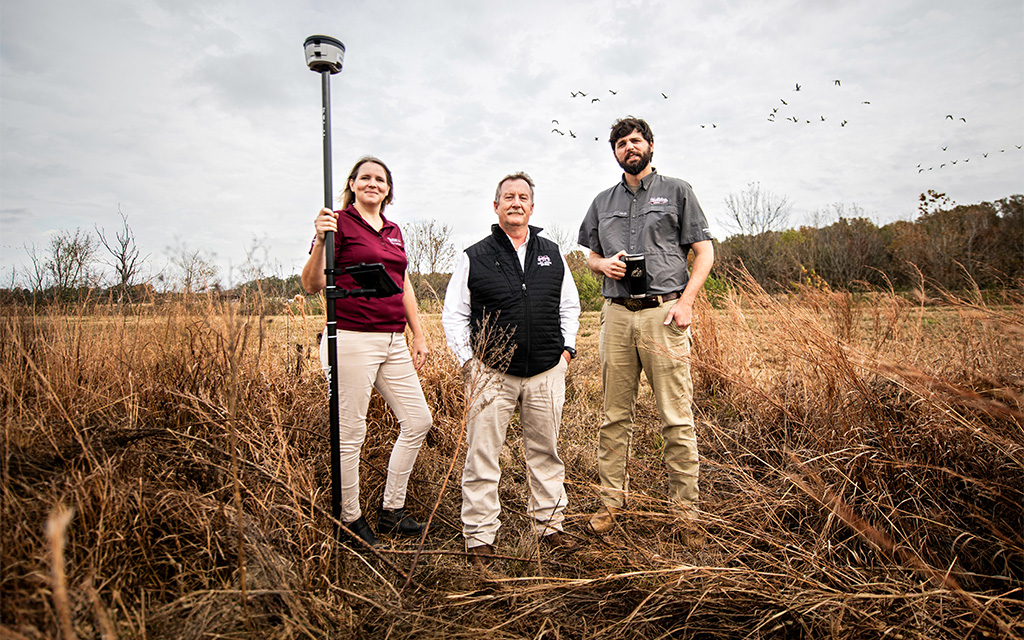

Led by precision conservation pioneer Wes Burger, dean of the College of Forest Resources and director of the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, MSU research is developing the tools and methods that will protect natural resources for future generations.

“Precision conservation aims to increase profit on working lands, while also precisely measuring the affected ecosystem services those areas provide, including value to wildlife and mitigating greenhouse gases,” Burger said.

It’s a balancing act between helping landowners use and profit from their investment while allowing natural systems that benefit the earth to remain in place.

“Just like precision agriculture, precision conservation is putting the right practice in the right place at the right time,” Burger explained.

Conservation in the field

Burger has studied working lands conservation since 1985, when the first farm bill to include the Conservation Reserve Program—an initiative to incentivize conservation—was passed. By the 1990s, he was helping landowners adopt conservation practices in working landscapes. Through this work, he realized one of the biggest barriers to targeted conservation was a lack of understanding.

“Complex conservation programs make it challenging for producers to visualize where conservation fits on the landscape,” Burger said. “It often takes an expert to understand programs and determine eligibility. Often, producers also don’t understand the costs or benefits of adopting conservation practices.

“I collaborated with landowners to help them understand where conservation made sense both environmentally and economically,” he continued.

Initially, Burger used geospatial technology combined with cropping data to determine eligibility at the field level. Each conservation practice has its own set of eligibility criteria and each field its unique set of characteristics. The process proved cumbersome.

“Think of your field as an investment portfolio. Some assets or areas are extremely productive; others are much riskier. Economically targeted conservation allows you to diversify your portfolio by taking that less profitable, risky ground and putting it in a safe bet where you’ll get a consistent return year after year.” ~Mark McConnell

“An individual field analysis took dozens of geoprocessing steps,” he said. “Evaluating one field was so complicated—an entire farm, even more so. We sought a simpler way.”

In 2009, when Burger was a wildlife professor, he hired Mark McConnell as a graduate student to help develop a user-friendly tool for geoprocessing. Having a farming background, McConnell immediately understood the inherent challenges and utility.

That work resulted in the tool used today.

McConnell, who earned MSU master’s and doctoral degrees in wildlife, fisheries and aquaculture science, is now a member of the Bulldog faculty as a wildlife assistant professor and continues to work with Burger.

Recently, the team launched the MSU Precision Conservation Tool, decision-making software that identifies precise locations where conservation practices are most financially beneficial to farmers.

“In a recent study, we found that economically targeted conservation increased revenue across 52 agricultural fields by about 24%,” McConnell explained.

That study, which evaluated fields in Lowndes County, was published in an international journal. It included evaluation of three scenarios: regular production, maximum conservation and economically targeted conservation.

“We showed that the benefit ranged from 1-250%,” he said. “As a farmer, I wouldn’t take land out of production for a 1% increase in revenue, but I’d begin with fields that show a 250% increase and work my way down for as long as it made economic sense to my operation.”

McConnell said he equates the process with a common investment strategy.

“Think of your field as an investment portfolio. Some assets or areas are extremely productive; others are much riskier,” he explained. “Economically targeted conservation allows you to diversify your portfolio by taking that less profitable, risky ground and putting it in a safe bet where you’ll get a consistent return year after year. You’ve reduced the economic risk on that field because your vulnerable farming areas now generate a consistent payment.”

McConnell said economically targeted conservation is gaining traction among farmers and wildlife professionals alike, noting the model created at MSU is used by Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever nationwide. He said he believes data collected through the software’s use can help inform future policy.

“We used our software to compare the last two farm bills and evaluate the economic impact of the same conservation action between two different policy structures,” McConnell said. “The difference is significant. As crop prices surge and policy shrinks applicable conservation areas, our tool finds eligible land to put into conservation in a manner that’s profitable to farmers.”

Mitt Wardlaw, an MSU agronomy alumnus, beta-tested the MSU software for 10 years. Wardlaw, one of the owners of Southern Ag Services, an agricultural consultancy firm, and Midsouth Resource Management, a land management firm, said the software takes the guesswork out of conservation applications.

“On the agricultural consulting side, we help growers make better decisions to increase profitability and sustainability. On the land management side, we seek to improve the land’s recreational value,” Wardlaw said. “This software assists with both as a decision support tool to help farmers and landowners make informed choices about whether to enroll a portion of their land in the farm bill’s Conservation Reserve Program.

“Any time we can make production practices more profitable while increasing the land’s recreational value, it’s a win-win,” he continued. “This tool allows us to do just that by evaluating those places that precisely align with Conservation Reserve Program opportunities.”

McConnell said he sees ample opportunity on the horizon for precision conservation.

“The U.S. has enough land to continually enroll acres in economically targeted conservation for my entire career,” he said. “That’s something people don’t realize. Nearly every farmed field has some sort of opportunity when it comes to this.”

Kristine Evans, who also earned MSU master’s and doctoral degrees in wildlife, fisheries and aquaculture science under the direction of Burger, leverages precision conservation technology in much of her research. As an associate professor in wildlife, fisheries and aquaculture, she recently began work on a CRP Menu tool with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Services Agency.

She said the USDA’s goal is to empower farmers to make informed decisions about enrolling their land in the conservation program, and that’s where MSU comes in. The CRP Menu is a user-friendly, web-based, decision-support system that helps break down the complexity of CRP practices and gives guidance for practices based on the landowner’s conservation goals and eligibility.

“We are taking the underlying infrastructure of our existing Gulf Strategic Conservation Assessment tool and expanding it regionally, and then hopefully nationally, to help guide farmers in their decisions on which conservation practices to enroll in,” said Evans, who is also an associate director of the Geosystems Research Institute.

While the MSU Precision Conservation Tool developed by Burger and McConnell primarily focuses on economically targeted conservation, the tool Evans is developing focuses on the holistic conservation goals a farmer is trying to achieve.

“This tool will provide the landowner with two options to explore the Conservation Reserve Program,” Evans said. “One will allow landowners to add in their priorities, and the tool will tell them what the best practices are in their county. The second part will have farmers identify their field boundaries and provide information like cropping history and slope. The tool will then tell them which practices may be best matched to their land.”

She said she hopes both this tool and the MSU Precision Conservation Tool can be tightly integrated.

“We hope a farmer can export their information from our tool right into the MSU Precision Conservation Tool to assess economic tradeoffs based on their real yield data and individual conservation priorities,” she said.

Like McConnell, Evans has a passion for conservation in agricultural landscapes.

“Agricultural conservation has been near and dear to my heart since I was in graduate school and leading a national effort to evaluate bird response to a CRP habitat practice,” Evans said. “It is exciting to be able to take the technology we developed in other regions and expand it to a whole new set of stakeholders in a whole new system.”

While the project is just ramping up, with farmer workshops scheduled in three states this year, Evans said she looks forward to the possibilities.

“Any time I can help deliver good science to the public in a way that can help individuals make smart, strategic decisions is a huge win for me,” she said.

Conservation in the forest

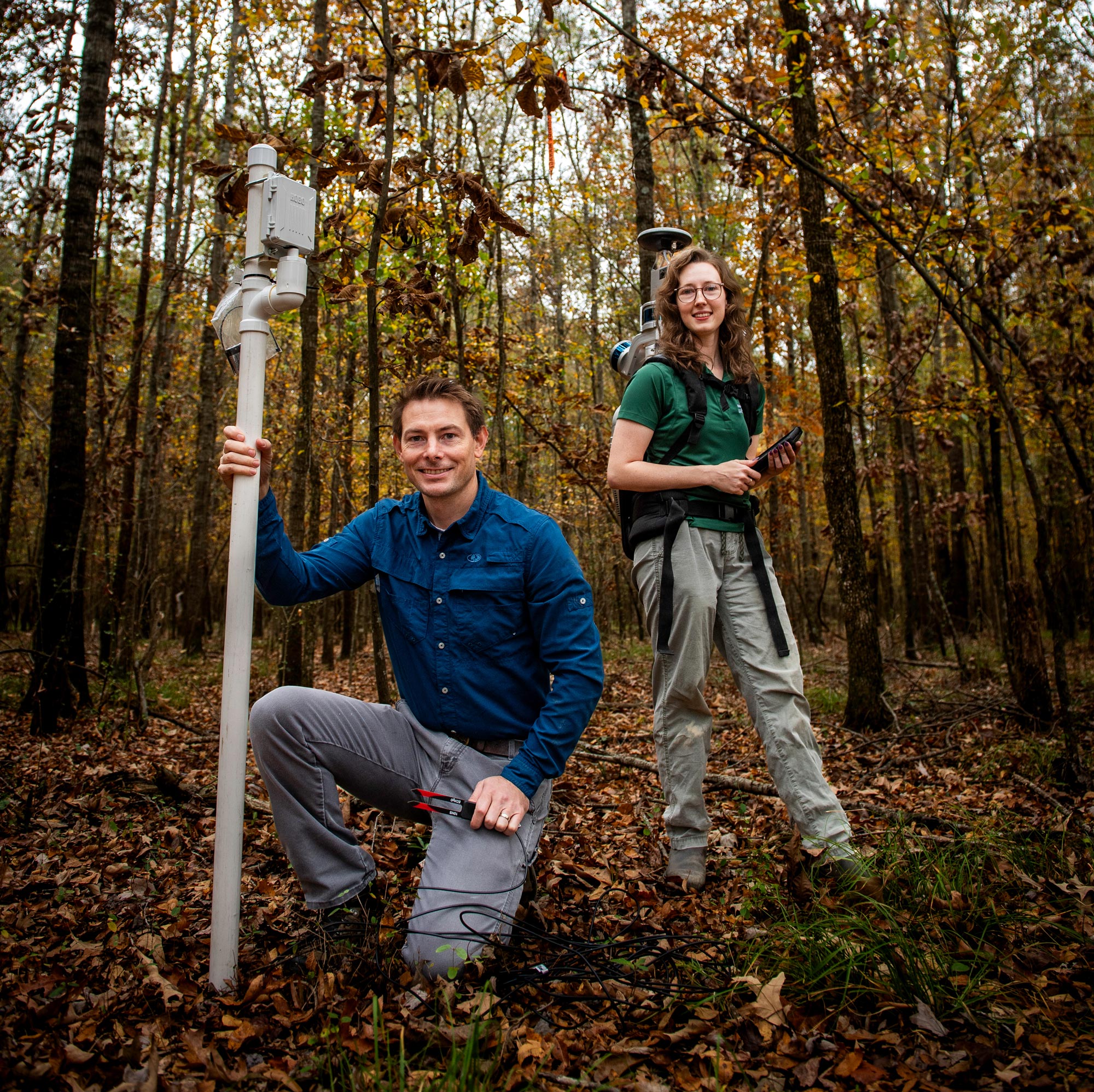

Working on the forestry side of the CRP, Austin Himes is evaluating how successful certain conservation practices are in reducing greenhouse gasses in the U.S. The assistant forestry professor is using precision conservation technology to evaluate how forests in the federal CRP can sequester—and store—carbon.

The project, which is halfway through its five-year run, is a nearly $3 million cooperative agreement with the USDA to calibrate the DayCent model, which is used to simulate greenhouse gas fluxes in the atmosphere. MSU, in partnership with Alabama A&M University, will evaluate hardwood and softwood CRP-enrolled tree plantings across eight states: Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky and Illinois.

“Forests in the Southeast sequester carbon at higher rates than almost anywhere in the country,” Himes explained. “The region also has 86% of the nation’s acreage under CRP tree-planting contracts.”

By collecting a broad sample of field data, the team will help calibrate, validate and improve on methodologies the USDA uses to estimate how CRP lands mitigate climate change, as well as other wildlife benefits.

“We hope a farmer can export their information from our tool right into the MSU Precision Conservation Tool to assess economic tradeoffs based on their real yield data and individual conservation priorities.” ~Kristine Evans

Himes said the DayCent model used by the USDA needs this vital information to build on.

“Most of the biomass data for trees comes from public and private forestland that differs from CRP lands in ways that affect productivity and tree growth,” he said. “There is a critical need to calibrate the DayCent model with data specific to CRP tree plantings to accurately estimate and value their climate change mitigation benefits.

“We have a backpack LIDAR we use to scan the area,” Himes said of the laser imaging technology used in the project. “This allows us to recreate the forest structure three-dimensionally and improve biomass estimates and thus get a more accurate picture of carbon stored in these forests.”

The team is also using dendrometers—precision sensors that measure the growth of plants—to measure daily changes in tree diameters and track them through time.

Adam Polinko, an assistant forestry professor, built dendrometers with data loggers using open-source technology for about 10% of the cost of the same technology available on the market. The tool lets researchers see snapshots of changes in the trees several times a day.

“I pieced things together from open-source materials, which excites me because building something useful and affordable from what’s available has value,” he said.

Natalie Dearing, a 2017 forestry graduate and current graduate student in entomology, serves as project manager of the DayCent evaluation research. She collaborates with landowners to secure sites and coordinates equipment installation with the project’s 11 principal investigators.

“I’m enthusiastic about these topics and enjoy working with our team. Diversity and collaboration with different people who bring different perspectives improve the science,” she said.

Himes said the work will go far in providing insight into how CRP forests help mitigate climate change.

“Mississippi leads the nation with more than 400,000 forested CRP acres,” Himes said. “I like to think of CRP as the largest afforestation project in the U.S. because we’ve converted more than 1 million acres into forestland. Understanding the impacts on global greenhouse gases of that shift is important and this research will show us that.”

By Vanessa Beeson, Photos by Grace Cockrell

Enrolling Land in Conservation

Demetrice Evans, a 2001 forest products graduate, has been with the Farm Service Agency for 15 years. He began as a county office trainee then moved through the ranks at the county, state and national levels. He now serves as the chief of Mississippi’s Price Support Division as the first African American to serve in this capacity.

“As with all FSA divisions, the Price Support Division strives to keep farmers and ranchers in business during tough times and provides them with the resources to be successful,” Evans said.

While the division offers a myriad of loans, disaster-relief assistance, cost-share assistance, indemnity programs and conservation programs, Evans said producers receiving benefits through FSA are required to meet the conservation compliance provisions.

“Conservation compliance requires producers to have a conservation plan approved by USDA if they plant annually tilled crops on highly erodible soil. Compliance also prohibits producers from planting on converted wetlands or converting wetlands for crop production. Non-compliance will affect USDA program benefits.”

Visit www.fsa.usda.gov/Assets/USDA-FSA-Public/usdafiles/FactSheets/2022/conservation_at_a_glance_22_final.pdf for a list of conservation programs offered by USDA’s Farm Service Agency and Natural Resources Conservation Service. Evans said the following FSA conservation programs are typically considered by eligible Mississippi producers:

Grassland CRP Signup helps landowners and operators protect grassland. The program emphasizes support for grazing operations, plant and animal biodiversity and eligible land containing shrubs and forbs under the greatest threat of conversion.

General Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) protects soil, water quality and wildlife habitat by removing highly erodible or environmentally sensitive land from agricultural production through long-term rental agreements. CRP landowners that have an expiring CRP contract are eligible for the Transition Incentives Program (TIP), in which they can sell or lease long-term to a beginning, veteran, or socially disadvantaged farmer.

Continuous Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) allows environmentally sensitive land devoted to certain conservation practices to be enrolled in CRP at any time. Also includes CLEAR30 and Safe Acres for Wildlife Enhancement (SAFE).

The Mississippi Forestry Commission also offers programs for landowners. Visit www.mfc.ms.gov/programs/private-landowner-services to learn more.