MSU researchers making advances in fight against cardiovascular disease

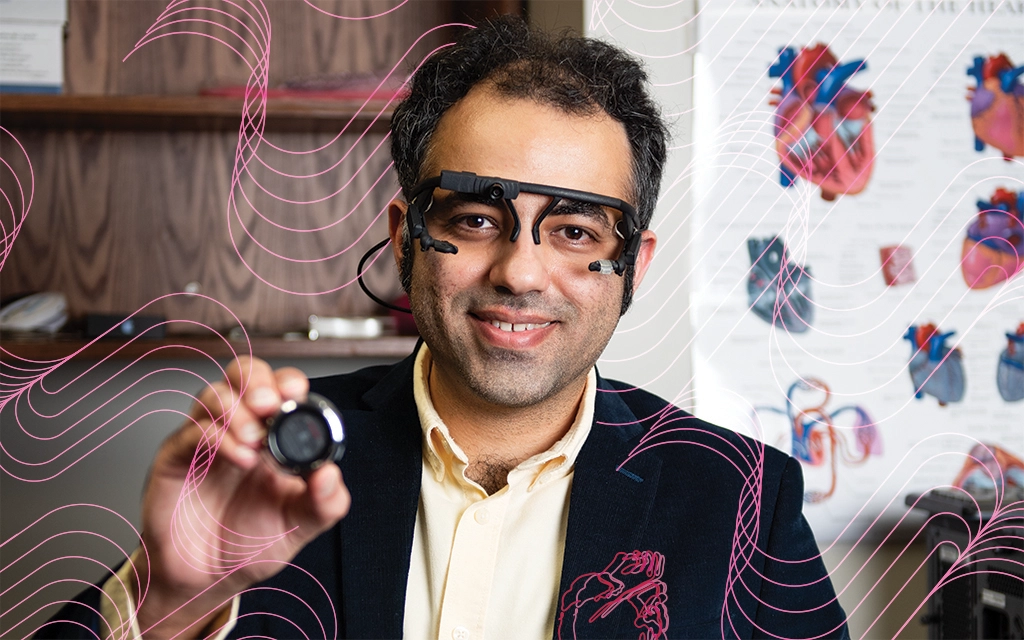

When Amirtaha Taebi joined Mississippi State’s biomedical engineering faculty in 2021, he also joined the fight against the world’s leading cause of death—cardiovascular disease.

Encompassing all conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels, including problems present at birth and those that develop over time, these diseases directly affect over half a billion people worldwide and cause cascading effects throughout families. For Taebi, cardiovascular disease is the reason he never met his grandfather and is something his mother is currently fighting.

“A few years ago, I realized my mother has a congenital heart disease. People often won’t notice these diseases until they are 50 to 60 years old,” said Taebi, an MSU assistant professor of biomedical engineering. “Once I heard about her condition, it made me even more motivated to work in the area of cardiovascular engineering.”

Using his personal connections to cardiovascular disease as motivation, Taebi is working to find solutions to the global, heart-health crisis. With funding from Mississippi State, he established Taebi Lab, which is dedicated to developing tools to improve cardiac health.

Housed in the Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, the lab includes graduate and undergraduate student researchers. Under Taebi’s direction, the team is working to develop new and more affordable methods for the early detection and monitoring of cardiovascular disease to improve the care of those in rural and low-income areas like Mississippi.

“We focus on cardiovascular diseases because they are not only the leading cause of death in United States but also in the world. One American dies from cardiovascular disease every 33 seconds,” Taebi explained, noting that Mississippi has the country’s second highest mortality rate from congenital heart diseases.

Taebi said his research also focuses on health equity because low-income, underrepresented populations are often more affected by cardiovascular diseases. By creating low-cost, easy-to-use tools, the researchers hope to make monitoring, as well as diagnostic and preventative care, more accessible.

“That’s why we want to create methods for cardiovascular monitoring that are accessible, low-cost and widely available to the general public, so even low-income individuals and those based in rural areas can use these devices to monitor their or their loved one’s cardiovascular activity,” Taebi said. “If something is wrong, they can know as soon as possible and see a doctor to determine their next steps.”

Taebi explained that vibrations in the human body, which are caused by one’s heartbeat, can be used to detect cardiovascular abnormalities. He said the lab is studying these vibrations to understand what cardiac events are represented by the pattern, or waveform, of the vibrations.

“If you place your hand on your chest, you will feel vibrations as a result of your heart pumping blood to different organs in your body. We can measure those vibrations using sensors,” Taebi explained.

“By analyzing those vibrations, we aim to help determine if your heart is working normally or atypically and, if it’s atypical, whether it’s a sign of disease and something that should be referred to a doctor,” he continued. “We want to detect problems as soon as possible to get medical intervention quickly.”

The ultimate goal, he said, is to reduce mortality rates, optimize medical therapy, reduce hospital stays and improve the lives of patients.

Sophia Ruckman, a senior biomedical engineering major from Hoover, Alabama, works as a student researcher in Taebi Lab, researching methods to monitor some of the same cardiovascular diseases she lives with.

As a child, she was diagnosed with and underwent surgery to repair a coarctation of the aorta and transposition of the great arteries—two potentially fatal congenital heart diseases.

“Whenever I would go to my doctor, he would always tell me about the cardiovascular research being done, because it was a very hard surgery to survive at the time,” Ruckman recalled. “I was one of those people who was able to go play soccer and be active, but a lot of people who came back from those surgeries were living very minimal, limited lives.”

She said she appreciated learning about the science that allowed her to live her life fully, and after telling Taebi her story, he invited her to join his research team.

She joined the lab in 2022 and began researching how to create a low-cost heart monitor that individuals can keep at home to track cardiovascular activities, including the electrical and mechanical aspects, blood oxygen levels and heart sounds.

Ruckman said the first step in creating the monitor was determining the feasibility of such a device using inexpensive sensors and a microcontroller—a small computer designed to perform a specific task.

“We tested our first prototype on a few human subjects in spring 2023,” Ruckman said. “Then, we were able to write a paper and present our research at a few conferences this past semester.”

Ruckman said that after their initial research, the team was able to determine the feasibility of the device and develop a plan to make it wireless. The team also plans to survey doctors and patients for feedback on the appearance of the monitor, which can affect patients’ willingness to use the device.

“We hope to create a device that can give patients information they would be able to understand,” Ruckman said. “Patients could use the information and go see a doctor if they needed more care.”

Along with developing a low-cost heart monitor, the Taebi team is working on an accessible smartphone app for cardiovascular monitoring.

“Around 80% of Americans have a smartphone, meaning that in most households, there is at least one person with one,” Taebi said. “Once we release the app, most Americans will have access to a cardiovascular monitor in their pocket or in their home.”

By Aspen Harris, Photos by Grace Cockrell

KNOW YOUR HEART

While there is no substitute for regular checkups and monitoring by a health care professional, the Cleveland Clinic offers the following tips to identify compromised cardiovascular health.

The following could be signs of heart disease:

• Chest pain, called angina in health care settings

• Chest pressure

• Shortness of breath

• Dizziness or fainting

• Fatigue or exhaustion

Symptoms of blood vessel blockages include:

• Pain or cramps in the legs when walking

• Leg sores that are not healing

• Cool or red skin on the legs

• Swelling in the legs

• Numbness in the face or a limb, often on one side of the body

• Difficulty talking, seeing or walking

It is recommended you seek medical care or call 911 if you or someone you love is experiencing any of those symptoms. The Cleveland Clinic also provides the following lifestyle management tips for lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease.

• Avoid all tobacco products

• Manage other health conditions such as diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure

• Maintain a healthy weight

• Limit intake of saturated fat and sodium

• Exercise at least 30 to 60 minutes most days

• Reduce or manage stress