The late-born son of a WWII prisoner of war, I knew that children were supposed to be “seen and not heard.” I never mastered that command.

Though “ADD” before the disorder was cool, I knew to keep my butt still and my mouth shut when my father and his buddies swapped tales of growing up in the Great Depression or surviving the war. They were all great storytellers.

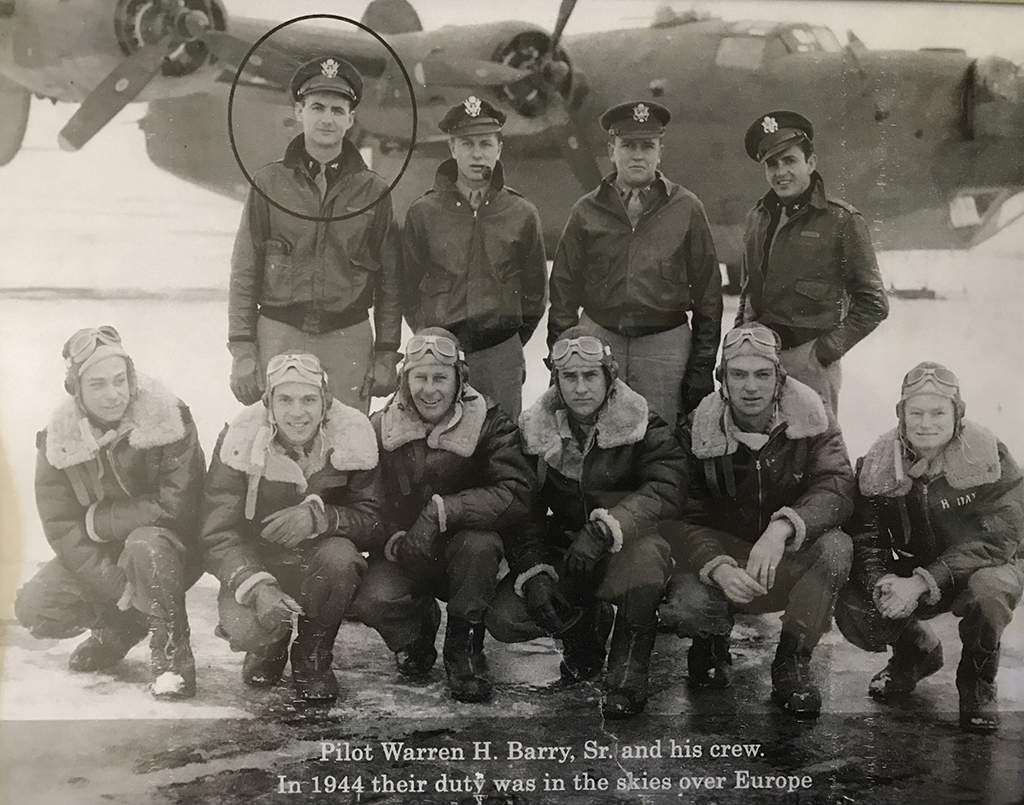

Years later I sat down with my father, Warren Barry Sr., and recorded many of his stories. He talked mostly of love and war. He married the love of his life, Dorothy Sykes Hall of New Albany in the spring of 1943.

By the spring of 1944, Mom was a coed living in a sorority house on the campus of Ole Miss, and Dad was a pilot flying a B-24 bomber out of the Eighth Air Force in England. He was shot down over Germany on his fourth mission.

What follows is Dad’s account, at times spurred on by my questions, of his miraculous survival, his lonely first night as a POW, and the hope he found the next morning. The hope he found in “Go to Hell Ole Miss.”

“Dad, tell me about your first night in Germany,” I said.

“Loneliest night of my life,” he said.

“Didn’t everybody jump out together?”

“I knew my plane could blow any second after two of her four engines caught fire. Ordered the crew to bail out while I did my best to hold her steady.”

“How far did you make it after they bailed out?”

“Not far. Three German fighters were closing in for the kill when I found myself over a dark blue lake that looked like it belonged in some other world. All of a sudden, they pulled up and flew away. I never saw ‘em again. Had no idea why they’d backed off until I made it to prison camp and found myself in a serious interrogation with the American boys.”

“Americans?”

He nodded. “Germans planted spies in our camps. Toward the end I was telling them about the lake when this colonel piped in, ‘Son, that lake saved your life. It’s where the Germans are making heavy water for their nuclear program. Most heavily defended facility on the planet. You must’ve been flying so low they were late picking you up and couldn’t risk you going down and tearing up the place. Lieutenant, you gotta be the luckiest man in the war!’”

“What a miracle,” I said.

“But not the first.”

“What happened after the lake?”

“I was closing fast on 2,000 feet and knew my chances of the plane holding steady long enough to unhitch my gear, scramble out of the cockpit, and bail out were next to nothing.” Dad paused, staring at the floor. “But then the strangest thing happened. I heard a voice saying, ’Don’t worry, young man. I’ve got plans for you.’ God took care of me, and sure enough I made it.

“Wasn’t long before I hit the ground with a thump that knocked off my boots. Buried my chute and ran for a patch of woods but didn’t get far. Germans had seen the whole ordeal and come my way. They hollered and sent a few bullets over my head for good measure.

“They locked me in a farm shed that first night. It was a night I’ll never forget. Feeling guilty for losing my plane, worried sick over the other nine boys in the crew, cold and missing my wife, I hunkered down and leaned against the wall.

“At daybreak my chin was dragging so low I could hardly see my feet. Sun went to rising and sending beams of light through cracks in the wall I was propped against. Felt the sun warming my back, watched it light up my boots and inch its way up the far wall. And there it was: Go to Hell Ole Miss.”

“What are the odds,” I said, wishing I had more to say. “What a story.”

“My best story,” he said with a chuckle. “My favorite anyhow. Sure lightened my load knowing a fella from back home had walked my path. And had the gumption to slip a knife past those Germans and give our Ole Miss buddies a piece of his mind.”

“A Mississippi State Bulldog!”

Dad nodded and gave an easy smile. “The good Lord was taking care of me. Tossing a pebble of hope my way. More than a pebble, I suppose.”

A native of North Mississippi, Jeff Barry grew up with family on both sides of the rivalry between Mississippi State and Ole Miss, including his cousin Franklin Evans who played for the Bulldogs under Head Coach Bob Tyler in the late 1970s. He, however, found his undergraduate home at fellow Southeastern Conference institution Vanderbilt, where he played tennis in the late 1980s.

In the story recounted above, the unofficial Bulldog fan battle cry offered a beacon of hope to a GI caught behind enemy lines and showed the tenacity and unerring spirit of the Maroon and White faithful. It also provided inspiration and a title for Barry’s national bestseller “Go to Hell Ole Miss.” Set in a fictional, rural Mississippi town, this debut novel is a “historical family saga of hope and hardship, redemption and revenge, faith and doubt” that has received comparisons to the works of Pat Conroy and Cromac McCarthy.

Barry’s book, “Go to Hell Ole Miss” is available online and in select bookstores. Visit Jeff-Barry.com for more information.