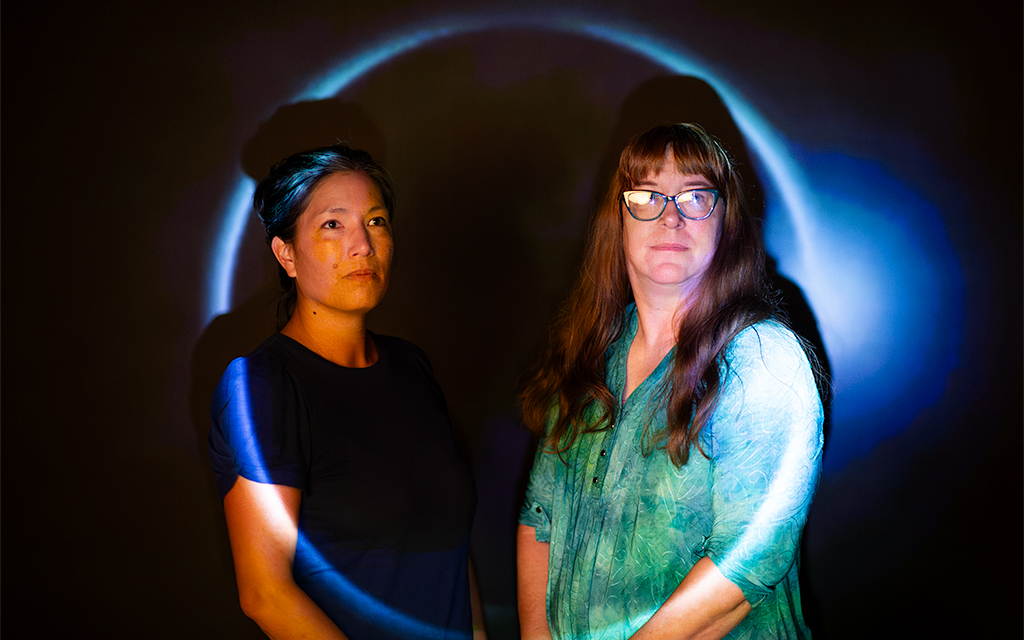

What happens in the heavens matters on Earth. That’s the message of two MSU faculty—historian Alexandra Hui and astrophysicist Angelle Tanner.

From humans observing the movements of celestial bodies to hurling manmade objects into and beyond the exosphere, space events—and the science behind them—have been tied to the culture of the people experiencing them throughout history.

Using the backdrop of April’s North American solar eclipse, the two associate professors illustrate the intersection of science and the humanities—and the importance of a well-rounded education, like that available at MSU.

“Events like a solar eclipse are intense moments of collective experience that are special and precious,” Hui said. “As historians, we’re always thinking about where we can find entry points into the past. These events—these very tight, specific moments in history—are that. Everyone gets excited, there’s lot of documentation and everyone’s experiencing them collectively.”

On April 8, almost 45 million people in Canada, Mexico and the U.S. were plunged into near darkness as the moon’s alignment with the sun briefly caused a total eclipse. Totality like this was observed in 15 American states, six Mexican states and six Canadian provinces. An estimated 650 million people—almost 8% of the world’s population—observed a partial eclipse despite not being in the path of totality.

Because the event, also known as the Great North American Eclipse, was observed by so many, it became a shared phenomenon, finding its way into the media, culture, dialogue and experiences of the day.

Since astronomers began successfully predicting when eclipses would occur more than 2,000 years ago, humans have been hooked on experiencing the phenomena. Now with the ease and eagerness of travel and the buzz generated on social media, more and more people want to see totality firsthand. This excitement has its positives. For example, economic forecasters at the Perryman Group predicted eclipse-chasing travelers would help generate approximately $4.6 billion of total expenditures in the U.S. states falling within the path of totality, which spanned from Texas to New England.

“Everyone was discussing why this eclipse was so different—why people were losing their minds over it—and I think it’s the fear of missing out, and the fact that FOMO can easily go viral. Things trend so quickly these days,” Tanner said. “Events like this show it’s very natural for astronomy and history—the humanities—to be interconnected.”

At MSU, the College of Arts and Sciences serves as the confluence of social sciences and the humanities—the academic disciplines focused on what forms and guides society and culture—and traditional sciences. Within the college are 14 departments and a variety of programs, centers and institutes available to students interested in the sciences that make up the world and how culture defines it.

Linking the two sides—how both science and the humanities inform and impact each other—is an important part of Hui’s and Tanner’s teaching at MSU. Hui is a historian of science who previously served as co-editor of Isis, a University of Chicago Press academic journal that explores the histories of science, medicine and technology, and how they’re influenced by and impact culture and society.

An accomplished astrophysicist who in 2020 helped announce the discovery of a new planet orbiting a star almost 32 light years away, Tanner is part of a roughly $20 million NASA space mission team that will put an artificial star in orbit around Earth for scientists to calibrate telescopes with to better measure the brightness of stars.

“What historians and astronomers do is not so different, especially in terms of thinking about how we frame the questions we ask and how we accumulate evidence that lives up to rigorous testing, debate and replicability. Science is often challenging to the status quo and has to defend itself against critiques that are political, social or cultural,” Hui said. “The humanities are everywhere, and science doesn’t work without people; it can’t be completely separated off from the humanities.”

As scientists continue tackling the hot-button issues of the day, historians document how we handle these challenges, Tanner said, explaining that both camps are similarly charged with “fighting to keep misinformation from affecting progress.”

“You have to pay attention to your sources. The key part of it all is scientific literacy. You have to broaden your horizons in terms of what you take in,” Tanner said. “Some things get sensationalized, and some people tend to stick to their self-confirming circles of information. They don’t take the time to seek out other sources of information, and we don’t make it easy for them at times.”

“What we think we know is always changing,” Hui added. “It’s our job to present the way knowledge about the world is created, practiced, shaped and maintained, and to show the roles of technology and culture, and how everything is connected.”

Both professors said MSU and its leadership create an environment that encourages instructors in different fields to collaborate and share ideas. This connectivity allows for better instruction throughout the university.

“From the president and provost to the deans and department heads, I think the general culture of Mississippi State is one that’s open and curious about interdisciplinary studies,” Hui said. “I have conversations with faculty from across campus about what I do and what they do, and I think there’s a friendliness and curiosity here that is unique.”

Story by Carl Smith, Photos by Grace Cockrell